Yemen's Mocha Coffee Can Spark Economic Growth

This post is Part I of a five-part series on measuring Al Mokha's impact in Yemen.

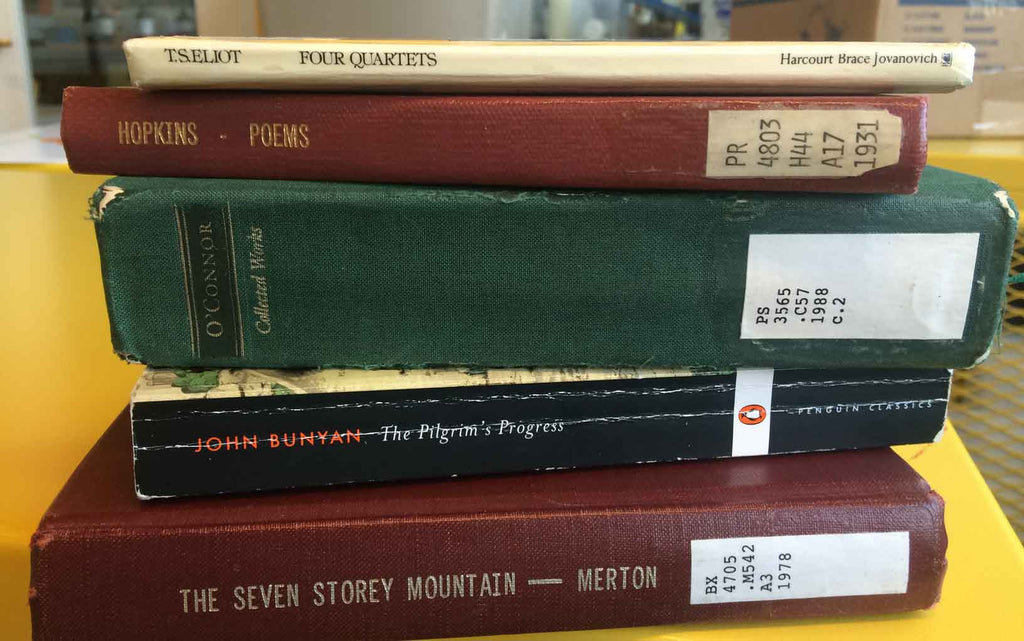

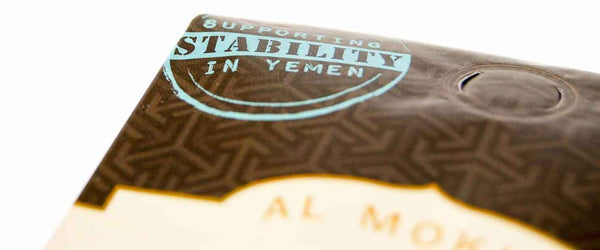

Two years ago, I founded a two-pronged enterprise with goals to be a successful coffee retailer and an entity that used our economic engine for the benefit of the people of Yemen. We call ourselves Al Mokha, Public Benefit Corp. and we source and market Yemen's World’s First Coffee™.

It has taken me two years to wrap my head around Al Mokha’s identity. Was I a coffee company? A development organization for a third world country? The reality is we are both, a startup with two faces; just like the Roman god Janus.

Let me illuminate.

We have two customers. The first is you, the consumer, and our product is our World’s First Coffee™. Our second customer is implied, and that’s the people of Yemen. If you turn our World’s First Coffee™ inside out, our product is life changing jobs. And here we can disappear down an academic rabbit hole.

A couple months ago I spoke with an investor who, after looking at Al Mokha’s meek sales numbers, tore me apart. She told me, “You’re an academic not a salesperson.” Put the books away and start selling! And go take a business course at a community college and meet with a business advisor at an SBA office.

Never mind that I spent a year in-residence at the Harvard Innovation Lab and I have a Harvard Business School / McKinsey consultant on my advisory board.

But here’s the remarkable thing about being an entrepreneur: name brand education and working hard doesn’t matter. It’s about results. Everything else is failure. You learned something? Whoop-dee-doo. You put in a ton of effort? Cool man. The business flourishes on sales that grow and the business starves on hard work that goes nowhere.

The investor was right. She looked at Al Mokha and frowned at our sales of $1000 per month.

For a business two-years-old our bottom line seems to mumble "maybe we'll be something someday." The investor rightly tore me a new one.

In her eyes, and in the words of the eminently hilarious HBO show Silicon Valley, Al Mokha’s product is our stock price and our purpose is driving it upwards.

Her attack—vicious if I lacked thick skin—captured precisely one-half of our double-bottom line.

The other half of Al Mokha is our social mission. And true to form, I have wolves prowling around the fringe there too, snarling at any sign of weakness. Michel, one of Al Mokha’s advisors, repeats himself when he says, “I’m just not sure about your claim on every single coffee bag. You claim ‘Supporting stability in Yemen’ but what proof do you have?” Or the words of Greg Olson, a USAID Implementing Partner Manager for a landmark 2005 survey of the coffee sector in Yemen. In an email he said, “My concern is how you are using the approaches identified in the past to strengthen the coffee value chain.”

Every direction I step there seems to be thorns.

But that’s not the whole story; I’m also surrounded by roses. Just today a random 500-word email from Tom Shess, an adoring customer. Here’s a tiny excerpt: “As a coffee lover, I have a list of favorites and your Yemen grown beans are among my top three.”

Or Hanan Yazid, a Yemeni American: “As a Yemeni woman who understands the power of business as a formidable tool to build bridges between people and to foster peace, understanding and harmony, I would like to commend you for thinking outside the box.” She gets it, our social mission.

What I failed miserably at explaining to the investor were the two faces of Al Mokha. As I, in her words, am an academic, let me call this our Janus business model. Yes, Janus the Roman god that has two faces and has given us the month of “January”. Janus is known for looking to the future and drawing from the past, and is the god of transitions. Our view of development is that our customers (you and your farming counterpart!) are inseparable, with Al Mokha in the middle.

As a development startup our role is tricky. In some ways we can consider our role as an intervention we are fine tuning. We know that markets can create wealth for both of our customers, the question is how do we operate in the middle.

One model is Fair Trade. But sometimes that leaves farmers and/or their workers poorer than their “Free Trade” peers.

Another model is Direct Trade. But is that scalable? And perhaps it’s like farmers markets in the US where I can attest you work your butt off and hardly make a decent wage.

A third, turbo-charged model might be capitalism. In Vietnam communism fell and the coffee sector rocketed from virtually zero to the second largest in the world. While Vietnam produces Robusta coffee and Yemen Arabica coffee, the takeaway is much the same: under the right model, rapid growth is possible.

If Yemen could replicate Vietnam's feat they would double their GDP.

Or consider a final model: In 1450, Yemen introduced coffee to the world. Al Mocha was the home port and now coffee is everywhere. Let’s harness that magic.

Al Mokha’s purpose in Yemen is life changing jobs—notably it’s not coffee jobs. Our focus is durable economic growth sparked by coffee. In this sense, our job is academic. As a startup, we must apply cutting-edge economic research and cutting edge technical innovations to something very old.

Our job is leveraging your desire for good coffee so it has maximum impact. We want a longer lever. Whereas one development model might have a 1x social return another model might have a 10x impact. Our business model is searching for this impact. We really do want your bag of coffee to change the world.

Those interested in trying Yemen's coffee can shop at www.almokha.com

Anda is the Founder of Al Mokha, Public Benefit Corp. He is a graduate student at Harvard University Extension and Air Force veteran. Part II - V of this series will be written by Erin Fletcher, Al Mokha's Board Advisor in developmental economics.

Also in Al Mokha Blog

The Secret to the Best Possible Mocha-Java Blend

by Anda Greeney

If you’ve been hanging out with us at Al Mokha for some time, you know that "Mocha" or "Mokha" means coffee from Yemen. And you’ve heard the story before: coffee cultivation started in Yemen circa 1450 and shipped from the port city of Al Mokha; and that’s how place name became synonymous with product.

Similarly, if you scratch your head a moment, you may think, hmm…maybe "java" literally means coffee from the Indonesian island of Java. And you’d be right.

Not only that, but you would be putting your finger on the “world’s second coffee™”. In about 1699, the Dutch East India Company began cultivating and exporting coffee from Java. This new origin ended Yemen's 250-year monopoly.

So there you go, and it’s pretty obvious how you would end up with a blend. Take Mokha + Java—i.e. world’s first and second coffee—and voila, "Mocha-Java," the World’s First Blend™. This is hardly a complex mathematical equation.

Is a $1 Billion Coffee Sector in Yemen a Good Idea?

by Erin Fletcher

In my last post, I talked about numbers, about progress and about impact we could measure at Al Mokha. Economists tend to get wrapped up in numbers. This group of people is richer, you might say, and an economist wants to know, okay, but how do measure “rich”? Is it how much money or how many assets they have; is it how much they earn? How do you get a representative sample to answer your questions? How do you know that someone’s observable (or unobservable) characteristics aren’t influencing the way they perceive the question?

Economists have largely settled these questions. With a little effort, you could get to a point where you could measure “rich” satisfactorily, where you could answer the question of who is richest.

But some questions are simply unanswerable within the paradigm of statistical causality. Some of those questions are ones that Al Mokha wants to answer.

For instance, is coffee the best answer to Yemen’s woes?

Yemen's $1 billion Coffee Opportunity

by Erin Fletcher

As a development economist with interests that are a little outside the norm, I spend a lot of my day thinking about how to measure unmeasurable things. How prevalent is a certain belief? And how does it affect people’s behavior? Can one violent event, or experience, be objectively seen as worse or more violent than another? And if so, what determines that violence—scope, tenor, frequency? How do we fix it?

So, when Anda told me he wanted to start thinking more about impact and measurement at Al Mokha, I jumped up and down with glee. From the moment he and I first talked development and coffee in Cambridge almost a year ago, I’d been questioning, "cool, but how do you measure that?"

Anda Greeney

Author