The Secret to the Best Possible Mocha-Java Blend

If you’ve been hanging out with us at Al Mokha for some time, you know that "Mocha" or "Mokha" means coffee from Yemen. And you’ve heard the story before: coffee cultivation started in Yemen circa 1450 and shipped from the port city of Al Mokha; and that’s how place name became synonymous with product.

Similarly, if you scratch your head a moment, you may think, hmm…maybe "java" literally means coffee from the Indonesian island of Java. And you’d be right.

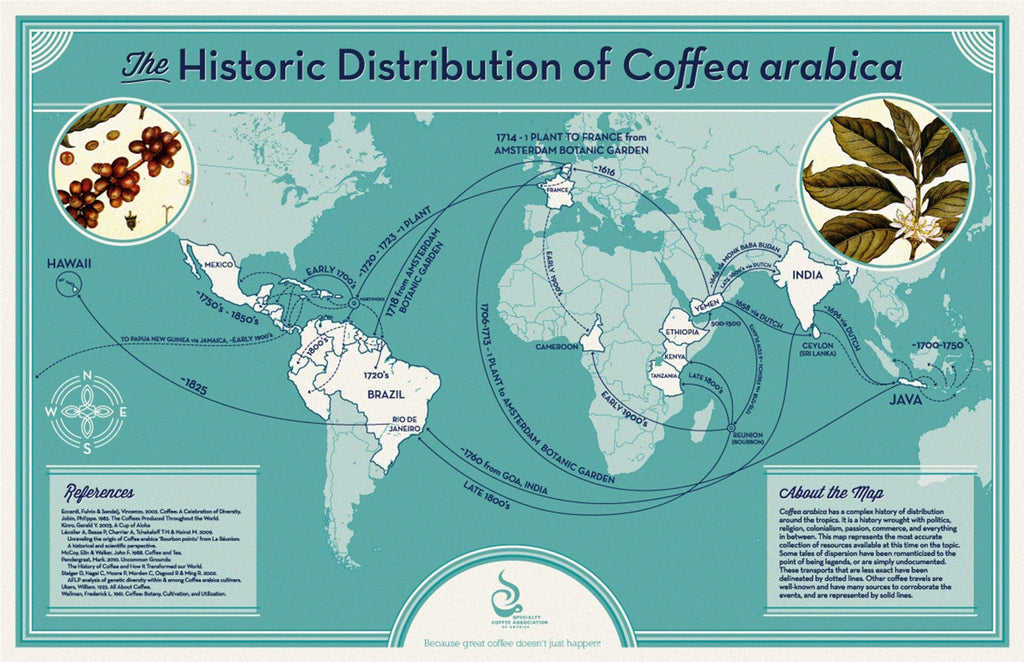

Not only that, but you would be putting your finger on the “world’s second coffee™”. In about 1699, the Dutch East India Company began cultivating and exporting coffee from Java. This new origin ended Yemen's 250-year monopoly.

So there you go, and it’s pretty obvious how you would end up with a blend. Take Mokha + Java—i.e. world’s first and second coffee—and voila, Mokha-Java, the World’s First Blend™. This is hardly a complex mathematical equation.

You may have heard of a Mokha-Java, but if not, understand that it’s the most famous coffee blend out there.

Early 20th century Mocha-Java mass branding & advertising.

That's a Sufi monk drinking coffee.

At Al Mokha we keep things straight forward: our "Mocha-Java" is a 50/50 mixture.

You might be asking yourself, if this blend is so darn famous and the first one of them all, why have I never heard of it / why is it so hard to find?

There’s really two reasons for this. First, coffee from Yemen is kinda hard to procure these days, so that tips the scale towards imitations. In my opinion, however, that’s hardly an excuse. If the recipe is Champagne and sunshine, then get me some capital-C Champagne and sunshine! (Sparkling wine is good, too, but don't tell me it's Champagne!)

The second reason why the blend is nearly impossible to find is way more important. Hold on tight.

"Mocha" + Java is simple enough, but as you know, these words are rather hard to pin down. If you went into your local coffee shop and ordered a "mocha" you’d end up with some sort of coffee and chocolate mixture. And if you ordered some java, you’d get a generic cup of coffee. Yet if you ordered a "Mocha-Java" you'd get a Yemen-inspired + Java-inspired cup of coffee; this, rather than a blend of the coffee-chocolate mixture + generic coffee. Ahhh!

Let's pause a second. You may have noticed me vacillating between spelling things "mocha" vs "Mokha". For clarity (and by fiat) "Mokha" with a "K" means coffee from Yemen. Thus, Mokha-Java has only one possible recipe. In contrast, "mocha" (and lowercase "java") has complicated baggage and ambiguous meaning.

Commercial coffee cultivation spread from Yemen to Java, with intermediate non-commercial stops in India and Ceylon.

Somehow, these Mokha and Java words describing origin abandoned their geographic roots, and we have to create new spellings of "mocha" to circle back to the original meaning.

If I want to make this linguistic frustration sound exciting and subversive, imagine a poorly organized cabal of coffee exporters, wholesalers, and retailers. To make more money, they spent the last three centuries leveraging the brand names of Mokha and Java by slapping these names on coffees not from these places.

Here's one example of pushing back against such a practice. In 1906, the U.S. Congress established the Pure Food and Drug Act. This act required that coffee be labeled by its port of departure. Good for Yemen, right? However, I want you to think like a subversive businessman. The obvious work-around is to ship, say, Brazilian coffee via the port of Mokha. This sleight of hand means the final port of departure was…Mokha. Enjoy your "Mokha" coffee.

And your game of whack-a-mole continues.

This dilution of meaning for Mokha and Java is why the real thing is hard to find: the ingredients are expensive, and linguistically, as Mocha and Java changed meaning, the recipe changed as well.

That’s how you end up with such “inspired blends”. You take these Mokha + Java impersonators and blend them together. Most frequently, roasters go with an Ethiopian + Sumatran. The Ethiopian will (should!) be a dry processed coffee like Yemen’s. And the Sumatran will come from the island of Sumatra, a mere ferry ride from Java. This is simple enough, but occasionally you’ll end up with wacky things like Colombian beans in the blend.

You can imagine where I am going. If you want the real thing, shop with Al Mokha. Our Mokha-Java is authentic and geographically accurate.

But no, no, no! It's not that easy. Let’s assume that getting the ingredients right—rather than being the end point—is the starting point!

Once there, how do you get the Mokha-Java blend to take flight? I’m talking the kind of coffee that not only tastes amazing, but inspires as well. That’s a tall order for some bean juice, but let me give it a go.

When I approach the philosophy of blending, it’s not just about historical accuracy. If it were, I’d source the proper historical origins and then I’d huddle over a historic open fire or antique cast iron stove. I would sweat profusely while stirring some coffee beans as they roasted unevenly and pungent smoke filled the coffee shop. For extra authenticity, I’d surround myself with arguing men wielding the best political pamphlets and broadsides of the day. Long live King George! You could bring the kids to this historical reenactment, circa 1720, pre-industrial revolution London. The proper quote to describe the coffee would be, “blacke as soote and tasting not much unlike it” (the English poet, George Sandys).

London coffee shop, circa 1700, replete with open flame. On the left the coffee brews, and on the right the conversation stews.

London coffee shop, circa 1700, replete with open flame. On the left the coffee brews, and on the right the conversation stews.

This looks and sounds amazing, and is in some ways where I take inspiration.

Imagine that roasting process. For say a given “Yemeni Medium” you can imagine some of the beans would more closely align with a light or dark roast—or maybe even unroasted or blackened with heat. Magical for sure, but we can do better than that heterogeneous blend of light, medium, and blackened coffee that tastes like soote.

In our Al Mokha blends, we’ve cleaned things up, and we start with purely roasted light, medium, and dark. From there we curate the heterogeneous blend rather than leaving it to chance. This means multi-layered, cleaner and more resonant flavors in the cup. In effect, the bean takes center stage rather than the roasting process. So that's one way to get from 18th-century inspiration to a 21st-century blend.

Beyond that, we of course benefit from a supply chain that's far faster and more reliable than 300 years ago. The coffee quality is excellent.

There are so many ways to get from then to now, and we've only dipped our toe in the English Channel of the 1720s. How about the 1820s and 1920s as we travel around the world? In future blends, we will keep exploring how to get a Mokha-Java blend to take flight…or to take to the sea in a steamship, the newest technology of the 1840s!

That's about it. The secret to the best possible mocha-java blend is following the recipe of Mokha + Java and translating that London cafe headline drawing into a roasting style. Enjoy!

Also in Al Mokha Blog

Is a $1 Billion Coffee Sector in Yemen a Good Idea?

by Erin Fletcher

In my last post, I talked about numbers, about progress and about impact we could measure at Al Mokha. Economists tend to get wrapped up in numbers. This group of people is richer, you might say, and an economist wants to know, okay, but how do measure “rich”? Is it how much money or how many assets they have; is it how much they earn? How do you get a representative sample to answer your questions? How do you know that someone’s observable (or unobservable) characteristics aren’t influencing the way they perceive the question?

Economists have largely settled these questions. With a little effort, you could get to a point where you could measure “rich” satisfactorily, where you could answer the question of who is richest.

But some questions are simply unanswerable within the paradigm of statistical causality. Some of those questions are ones that Al Mokha wants to answer.

For instance, is coffee the best answer to Yemen’s woes?

Yemen's $1 billion Coffee Opportunity

by Erin Fletcher

As a development economist with interests that are a little outside the norm, I spend a lot of my day thinking about how to measure unmeasurable things. How prevalent is a certain belief? And how does it affect people’s behavior? Can one violent event, or experience, be objectively seen as worse or more violent than another? And if so, what determines that violence—scope, tenor, frequency? How do we fix it?

So, when Anda told me he wanted to start thinking more about impact and measurement at Al Mokha, I jumped up and down with glee. From the moment he and I first talked development and coffee in Cambridge almost a year ago, I’d been questioning, "cool, but how do you measure that?"

Meet Al Mokha's Economist who we stole from Harvard

by Erin Fletcher

In Part I, Anda wrote about the perils of trying to be a salesperson / academic, and how that duality plays out in the business: investors want to see sales growth whereas economists (me!) want to see real, measureable change in things like poverty levels, in coffee production, in anything we can quantify with data.

So we're working towards that. In this post, Part 2, I introduce myself and in parts III- V we tackle some tough questions.

Well, who am I? If you're here frequently you know Anda and you've heard mention of some of his advisors (as he spins tales of sinking all his time into a startup). I'm the nerdy PhD obsessed with data and development. I have a doctoral degree in economics. I spend most of my time reading and writing papers on violence against women and children and female labor force participation. In the headline photo that's me doing research for the IRC in Nyarugusu, Tanzania. Basically, I spend a lot of time thinking about very economist-y things like incentives.

Anda Greeney

Author